Transformée de Fourier¶

La transformée de Fourier est une opération qui transforme une fonction intégrable sur \(\mathbb{R}\) en une autre fonction.

Signaux continus en 1D¶

Deux espaces :

\(L^1(\mathbb{R}) = \left\{ f: \mathbb{R} -> \mathbb{R}; \ \int_{\mathbb{R}}^{} | f(x) | \ dx < + \infty \right\}\)

\(L^2(\mathbb{R}, \mathbb{C}) = \left\{ f: \mathbb{R} -> \mathbb{C}; \ \int_{\mathbb{R}}^{} | f(x) |^2 \ dx < + \infty \right\}\)

\(L^2\) correspond à l’énergie finie

On défini sur l’espace des signaux d’énergie finie \(L^2\) le produit scalaire hermitien suivant :

Où \(\overline{a}\) le complexe conjugué de a \(\in \mathbb{C}\).

\(\left\{ \begin{array}{ll} a = a_{1} + ia_{2} \\ \overline{a} = a_1 - ia_2 \end{array} \right.\)

Attention : On a bien \(\int_{\mathbb{R}} f(x)\overline{f}(x)dx = \int_{\mathbb{R}} |f(x)|^2dx \leq 0\) et nul ssi \(f = 0\)

Quelques propriétés sur ce produit scalaire :

Symétrie hermitienne : \(<f,g> = \overline{<g,f>}\)

Linéarité à gauche : \(<f+ \lambda h, g> \ = \ <f,g> + \lambda <h,g>\)

Semi-linéarité à droite : \(<f,g + \lambda h> \ = \ <f,g> + \overline{\lambda} <f,h>\)

Remarque : on appelle une telle application une forme sesquilinéaire hermitienne (à droite)

Définition :

Soit \(f \in L^1(\mathbb{R})\) et \(\omega \in \mathbb{R}\) La transformée de Fourier de \(f\) est définie par :

Ici, on passe du domaine temporel au domaine fréquentiel.

En posant la notation \(e_\omega = e^{2i\pi\omega t}\), on retrouve alors la forme suivante exprimée avec le produit scalaire précédemment défini :

Pourquoi retrouve-t-on le signe \(-\) devant \(2i\pi \omega t\) ? La transformée de Fourier utilise le produit scalaire \(<f,e_\omega>\), dans lequel on utilise le conjugué.

Remarque : \(L^1(\mathbb{R})\) contient des fonctions discontinues mais on a une condition d’intégrabilité.

\(TF(f)(\omega)\) est bien définie car

donc \(\forall \omega \ | \hat{f}(\omega) | \leq \int_{\mathbb{R}}^{} | f(t) | \ dt\) avec \(\omega\) la fréquence en \(Hz\)

Propriétés de la TF¶

Linéarité

Soit \(a,b \in \mathbb{R}\) et \(f,g \in L^1(\mathbb{R})\)

Démonstration :

Théorème du retard (translation temporelle)

Soit \(t_0 \in \mathbb{R}\) et \(f : \mathbb{R} \to \mathbb{C}\). On définit la translation de \(f\) par \(t_0\) : \(\tau_a(f)(t) \mapsto f(t-t_0)\)

\[ \widehat{\tau_a(f)}(\omega) = e^{-2i\pi \omega t_0} \hat{f}(\omega) \]

Démonstration :

Modulation ou Translation fréquencielle

Soit \(\omega_0 \in \mathbb{R}\) et \(f:\mathbb{R} \to \mathbb{C}\) On pose la notation suivante : \(f_{w_0}(t) \mapsto e^{2i \pi \omega_0 t}f(t)\)

Démonstration :

Dilatation du temps (changement d’échelle)

Soit \(a \in \mathbb{R}\) et \(f : \mathbb{R} \to \mathbb{C}\). On définit la dilatation de \(f\) par \(a\) : \(D_a(f)(t) \mapsto f(at)\)

\[ \widehat{D_a(f)} = \frac{1}{|a|} \hat{f}(\frac{\omega}{a}) \]Démonstration :

Pour \(a \geq 0\) :

Pour \(a<0\) :

Passage au conjugué

Soit \(f : \mathbb{R} \to \mathbb{C}\)

Démonstration : $\( \begin{align} \widehat{\overline{f}}(\omega) =& \int_{\mathbb{R}} \overline{f(t)} e^{-2i\pi \omega t}dt \\ =& \int_{\mathbb{R}} \overline{f(t)} \overline{e^{2i\pi \omega t}}dt \\ & {\small \text{par la propriété du conjugué : } \overline{z_1}.\overline{z_2} = \overline{z_1.z_2}} \\ =& \int_{\mathbb{R}} \overline{f(t) e^{2i\pi \omega t}dt} \\ & {\small \text{par la propriété du conjugué : } \overline{z_1}+\overline{z_2} = \overline{z_1+z_2}} \\ =& \overline{\int_{\mathbb{R}} f(t) e^{2i\pi \omega t}dt} \\ =& \overline{\int_{\mathbb{R}} f(t) e^{-2i\pi (-\omega) t}dt} \\ =& \overline{\hat{f}(-\omega)} \end{align} \)$

Si on se donne \(\widehat{{f}(\omega)}\) pour \(\omega \geq 0\), alors on connaît partout \(\widehat{{f}(\omega)}\). La moitié de l’information suffit.

Dérivation temporelle

Soit \(f : \mathbb{R} \to \mathbb{R}\) différentiable

Démonstration :

Rappel intégration par partie

\(\int_{a}^{b} F'.G\ dt = [F.G]_{a}^{b} - \int_{a}^{b} F.G'\ dt \)

Fixons \(M_1\) et \(M_2\) deux réels positifs.

par généralisation si \(f\) est différentiable \(p\) fois tq \(\forall i \in \mathbb{Z} : f^{(i)} \in L^2\) alors :

De plus, si \(\widehat{f^{(p)}}(\omega)\) est d’énergie finie, \(L^2(\mathbb{R})\) alors : \( \widehat{f^{(p)}}(\omega) \in L^2(\mathbb{R}) => (2i \pi \omega)^p \hat{f}(\omega) \in L^2(\mathbb{R}) \)

Dérivation fréquentielle

Soit \(f : \mathbb{R} \to \mathbb{R}\) , si \(f\) et \(tf\) sont intégrables dans \(\mathbb{R}\) c.a.d: \(f,\;t \to tf(t) \in L^1(\mathbb{R})\)

Alors la transformée de Fourier \(\widehat{f}\) est dérivable (c’est à dire \(\widehat{f} \in C^1\)) et on a :

Démonstration :

Posons \(g(t, \omega) = e^{−2i\pi\omega t}f(t)\), et calculons : \(\frac{d}{d\omega} g(t, ω) = -2i\pi t.e^{−2i\pi\omega t}f(t)\)

Cette dérivée est continue \(\forall t \) et de plus \(\frac{dg}{d\omega}\) est une fonction intégrable (car \(tf(t) ∈ L^1(\mathbb{R})\)).

Les hypothèses du théorème de la dérivation sous le signe de l’intégrale sont donc vérifiées, et nous avons : $\( \begin{align} \frac{d}{d\omega}\widehat{f}(\omega) =& \frac{d}{d\omega} \int_\mathbb{R} f(t)e^{-2i\pi \omega t}\ dt \\ &= \small {\text{dérivation sous le signe intégrale}} \\ =& \int_\mathbb{R} \frac{d}{d\omega}(f(t)e^{-2i\pi \omega t})dt \\ =& -2i\pi \int_\mathbb{R} t.e^{−2i\pi\omega t}f(t)dt \\ =& -2i\pi.\widehat{tf(t)}(\omega) \end{align} \)$

La gaussienne (issue de la loi normale)

Soit \(g_\sigma\) la gaussienne d’écart type \(\sigma \in \mathbb{R}^+\) $\( g_{\sigma}(x) = \frac{1}{\sigma \sqrt{2\pi}} e^{-\frac{x^2}{2\sigma^2}} \)$

TODO : calcul de \( \widehat{g_{\sigma}}\)

Convolution¶

Soit \(h,g \in L^2(\mathbb{R})\)

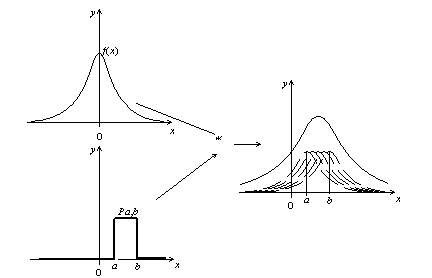

On définit la convolution h \(\ast\) g tel que :

Signal porte

On défini le signal porte \(\Pi_{[a,b]}\) part la formule suivante :

Par convention si a et b ne sont pas précisés alors \(\Pi(x) = \Pi_{[-\frac{1}{2}, \frac{1}{2}]}(x)\)

On a les propriétés suivantes :

\(\int_\mathbb{R} \Pi(t)dt = 1\)

Parité : \(\Pi(t) = \Pi(-t)\)

Propriétés¶

Commutativité : \(h \ast s = s \ast h\)

Bilinéarité : \((af+bg)*h = a.f*h+ b.g*h\)

Impulsion unitaire comme élément neutre : \(\mathbb{1}(t) = \left\{ \begin{array}{ll} 1 & \text{si } t = 0 \\ 0 & \text{sinon} \end{array} \right.\)

\(\int_{\mathbb{R}}^{}| f \ast g(t)| \ dt \leq \int_{\mathbb{R}}^{}| f| \ dt \ \int_{\mathbb{R}}^{}|g| \ dt\)

La convolution d’un signal \(f\) par le signal porte s’obtient en faisant glisser \(f\) sur l’intervalle \([a,b]\). On obtient alors un élargissement de \(f\).

Transformée de Fourier d’un produit de convolution:

Soit \(f,g \in L^2(\mathbb{R})\), on a :

Démonstration :

Inverse de la TF¶

Soit \(f \in L^1(\mathbb{R})\), On définit la transformation de Fourier inverse \(TF^{-1}\) par la relation :

Propriétés :

Symétrie : \(TF^{-1}(f)(t) = TF(f)(-t)\)

\(\widehat{fg} = \hat{f} * \hat{g}\)

\(TF^{-1} TF(fg) = fg\)

Égalité de Parseval¶

La TF préserve l’énergie des signaux. Isométrie de \(L^2(\mathbb{R})\)

Cela signifie, pour \(f : \mathbb{R} \to \mathbb{R}\)

L’énergie totale s’obtient en sommant les contributions des différents harmoniques

Transformation de Fourier en 2D¶

On considère \(L^2(\mathbb{R}^2,\mathbb{C}) = \{f : \mathbb{R}^2 \to \mathbb{C}; \int_{\mathbb{R}\times\mathbb{R}}|f(x,y)|^2 dxdy < +\infty \}\)

On définit la TF :

généralisation en dimension n :

Soit \(x = (x_1, \dots, x_n)\)et \( \omega = (\omega_1, \dots, \omega_n)\)

La plupart des propriétés déjà vues en \(1D\) restent vraies en \(nD\) cependant il y a quelques exceptions:

- \[TF(f(ax_1,ax_2)) = \frac{1}{|a|^2}\hat{f}(\frac{w_1}{a},\frac{w_2}{a})\]

- \[TF( \frac{\delta f}{\delta_{x_1}}) = (2i\pi\omega_1)\widehat{f}(\omega_1,\omega_2)\]

\(\frac{\delta}{\delta x_1}f\) indique une dérivée partielle. Cela signifie que l’on dérive la fonction par rapport à la \(1^{ère}\) variable uniquement en considèrent la seconde (ici \(x_2\)) comme constante.

Remarque :

Considérons le signal séparable suivant \(f(x_1,x_2) = h(x_1)g(x_2)\)

⚠ : En général, le signal n’est pas séparable.

Calcul de la TF du signal porte¶

Soit \(s(t) = \Pi_{[-\frac{T}{2}, \frac{T}{2}]}(t)\) avec \(T \in \mathbb{R}^+\)

On obtient alors un sinus cardinal.

On peut également s’apercevoir que \(s(t) = \Pi_{[-\frac{T}{2}, \frac{T}{2}]}(t) = \Pi_{[-\frac{1}{2}, \frac{1}{2}]}\frac{T}{t} = D_{1/T}(\Pi)\) Alors d’après la formule \(\widehat{D_a(f)} = \frac{1}{|a|} \hat{f}(\frac{\omega}{a})\)

et sachant que \(\widehat{\Pi}(\omega)= sinc(\pi\omega)\)

On obtient facilement : \(\widehat{s}(\omega) = T.sinc(\pi\omega T) = \frac{sin(\pi \omega T)}{\pi\omega}\)

Introduction aux distributions : masse de Dirac¶

Rappels sur Dirac :

Soient un espace mesurable \((X,{\mathcal {A}}\) et \(a\in X)\). On appelle mesure de Dirac au point \(a\), et l’on note \(\delta _{a}\), la mesure sur \((X,{\mathcal {A}})\) définie par :

où \(1_{A}\) désigne la fonction indicatrice de \(A\)

\(\delta _{a}(X)=1\) donc cette mesure est une probabilité sur \((X,{\mathcal {A}})\)

Par abus de langage, on dit que la « fonction » δ de Dirac est nulle partout sauf en 0, où sa valeur infinie correspond à une « masse » de 1.

Masse de Dirac : notation mathématique, définition de fonctions généralisées.

\(f \to f(x)\) évaluation en x, linéaire.

Si \(f\) est continue, alors :

On appelle Dirac en x, la fonction généralisée \(\delta_x\) et vérifie :

La distribution de Dirac, aussi appelée par abus de langage fonction δ de Dirac, peut être informellement considérée comme une fonction qui prend une « valeur » infinie en 0, et la valeur zéro partout ailleurs, et dont l’intégrale sur \(\mathbb{R}\) est égale à 1.

On dit qu’un signal correspondant à une distribution de Dirac a un spectre blanc. C’est-à-dire que chaque fréquence est présente avec une intensité identique. Cette propriété permet d’analyser la réponse fréquentielle d’un système sans avoir à balayer toutes les fréquences.

Propriétés :

IPP : soit \(f \ \mathbb{C}^\infty, f = 0 \ quand \ |x|>>1\)

Une autre façon de définir la masse de Dirac, c’est de dire :

qui est une limite de fonction

Pour \(f\) continue, \(f(t) \delta_0(t) = f(0) \delta_0(t)\) Avec \(g\) continue

Calcul de la TF de \(\delta_0\)

Dirac et convolution¶

L’« impulsion de Dirac » δ est l’élément neutre de la convolution

d’où : \(\delta \ast f=f\)

Dirac d’ordre supérieur : \(<\delta_0^{(1)},f> = f'(0)\)

Égalité entre deux distributions :

Soient \(\eta_1, \eta_2\), deux fonctions généralisées.

\(\eta_1 = \eta_2 = <h_1,f> = <h_2,f>\) \(\forall f \in \mathbb{C}^\infty(\mathbb{R}, \mathbb{C}) \ tq \ f(x) = 0 \ si \ |x| >> 1\)

Échantillonnage et théorème de Shannon¶

L’échantillonnage consiste à prélever à intervalle de temps régulier des échantillons du signal. Le signal devient alors périodique avec la \(T_e\) la période d’échantillonnage.

Motivation : étant donné un signal analogique \(s: \mathbb{R} \to \mathbb{R}\). On échantillonne le signal en \((nTe)_{n\in\mathbb{Z}}\)

Étant donné \((s(nTe))_{n\in\mathbb{Z}}\), peut-on avoir accès à \(s(t)\) ? \(\to\) non en toute généralité. Si \(Te << 1\), on aura une bonne approximation. Que se passe-t-il quand \(Te\) augmente ?

Théorème de Shannon :

Soit \(s:\mathbb{R} \to \mathbb{C}\) à bande passante \(\hat{s}(\omega) = 0\) si \(\omega \notin [-\omega_c,\omega_c]\) alors si \(Te < \frac{1}{2\omega_c}\), on peut reconstruire \(s\) par la formule d’interpolation.

Si on pose \(\phi_{Te} \ \text{le sinus cardinal} : \phi_{Te}=\frac{\frac{sin(\pi T)}{Te}}{\frac{\pi t}{Te}}\)

On peut donc écrire :

Problème : le sinus cardinal décroît lentement vers 0. Pour reconstruire f(t), on a besoin de beaucoup d’échantillons pour une bonne précision.

Hypothèse sur f :

\(supp(\hat{f}) \subset [-B,B]\) et \([-B, B] \subset [-\frac{1}{2Te},\frac{1}{2Te}]\)

On multiplie par une porte :

On applique \(TF^{-1}\) avec \(\phi_{Te}(t) = \frac{sin(\frac{\pi t}{Te})}{\frac{\pi t}{Te}}\)

On a donc :

\(\hat{f} = \hat{f_d}.h\)

et \(TF^{-1}(h)\) décroit vite car h est régulier.

On retient donc que sous des hypothèses de bande passante, on peut reconstruire exactement le signal échantillonné suffisamment rapidement. Ce théorème établit les conditions qui permettent l’échantillonnage d’un signal de largeur spectrale et d’amplitude limitées.

La période d’échantillonnage \(Te\) doit respecter la règle suivante : \(Te > 2f_{max}\). Si cette contrainte n’est pas respectée, alors on a un repliement spectral car le signal analogique et l’échantillonnage se superposent.

{\(f\) à bande passante} \(\subset\) signaux très régulier

\(TF(s)\) est le support dans \([-\omega_c,\omega_c]\)

Shannon en 2D¶

Si \(\hat{f}\) a un support dans \([-\frac{1}{2Te},\frac{1}{2Te}]^2\)

alors :

avec \(\phi_T : \mathbb{R^2} \to \mathbb{R}\)

Formule sommatoire de Poisson¶

La formule sommatoire de Poisson (parfois appelée resommation de Poisson) est une identité entre deux sommes infinie : sa première construite avec une fonction \(f\), la seconde avec sa transformée de Fourier \(\hat{f}\)

Soient \(a\) un réel strictement positif et \(\omega_0 = \frac{2\pi}{a}\).

Si \(f\) est une fonction continue de \(\mathbb{R}\) dans \(\mathbb{C}\) et intégrable telle que

et $\(\sum _{m=-\infty }^{\infty }|{\hat {f}}(m\omega _{0})|<\infty\)$

alors

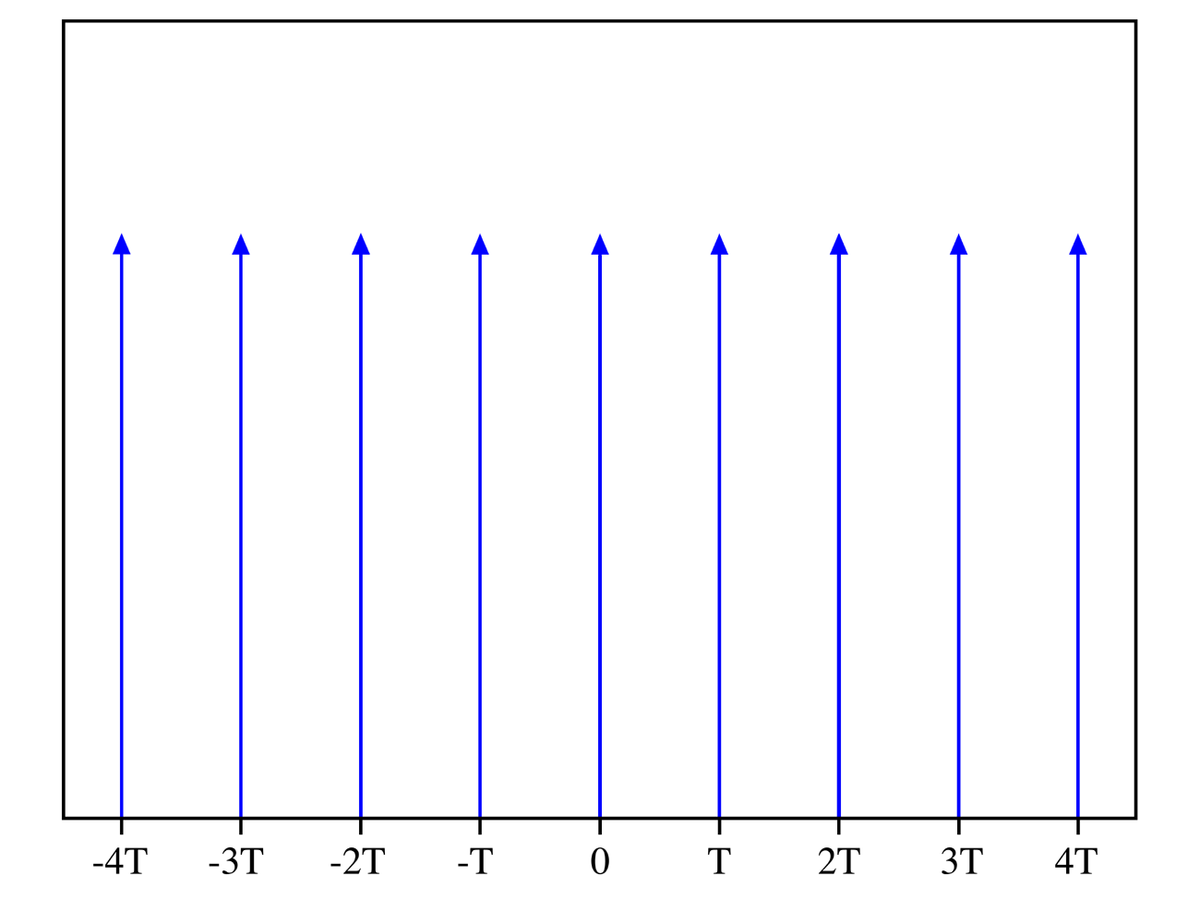

Peigne de Dirac¶

La distribution du peigne de Dirac est une somme de distributions espacées de

Cette distribution périodique est particulièrement utile dans les problèmes d’échantillonnage, remplacement d’une fonction continue par une suite de valeurs de la fonction séparées par un pas de temps \(T\). Elle est \(T\)-périodique et tempérée, comme dérivée d’une fonction constante par morceaux ; on peut donc la développer en série de Fourier.

Transformée de Fourier discrète¶

On se donne un signal de longueur \(N\) \((s_n)_{n=0,...,N-1}\)

\(\hat{s}(k)=\sum _{n=0}^{N-1}s(n)e ^{-2\mathrm {i} \pi k{\frac {n}{N}}}\qquad {\text{pour}}\qquad 0\leqslant k<N\)

Soit \(\omega = e^{\frac{-2i\pi}{N}}\) alors on a :

Soit s un signal périodique donc

sachant que \(A_{k,n} = (\omega^k)^n\), on a :

où T est la période du signal

Inverse de la TFD :

Soit une image f de taille M × N. La transformée de Fourier discrète inverse permet de calculer l’image originale à partir d’une transformée de Fourier :

où \(F(u,v)\) représente la TFD de l’image f.

Le produit de convolution de deux images est équivalent à la multiplication de leurs TFD.

TFD en 2D :¶

Fast Fourier Transform¶

On introduit l’algorithme de la FFT pour calculer la TFD car sa complexité varie en \(O(nlog(n))\) contrairement à l’algorithme naïf en \(O(n^2)\)

L’algorithme de la FFT est un algorithme qui permet d’effectuer la TF de manière plus optimale.

Lorsqu’on désire calculer la transformée de Fourier d’une fonction \(x(t)\) à l’aide d’un ordinateur, ce dernier ne travaille que sur des valeurs discrètes, on est amené à :

discrétiser la fonction temporelle,

tronquer la fonction temporelle,

discrétiser la fonction fréquentielle

La FFT est donc une décomposition par alternance de signal de \(N = 2^m\) points dans le domaine temporel en \(N\) signaux de 1 point.

Rappel sur la double somme :

Pour étudier la FFT à temps discret, on n’analyse pas ce qu’il y a au-delà de \(\frac{1}{2}\), on étudie le signal sur l’intervalle \([0;\frac{N}{2}]\)

Un exemple de la technique du zéro padding :

\(\vec{Y} = \begin{pmatrix} Y[0] \\ Y[N+M-1] \end{pmatrix}\)

Calculez \(Y[k]\) en faisant intervenir la TF \(X(\nu)\)

Soit \(\tilde{N} = N+M\)

\(Y[k] = Y(\frac{k}{\tilde{N}})\)

\(Y[k] = X(\frac{k}{N+M})\)

On a \(\frac{1}{N+M} < \frac{1}{N}\)

donc le pas d’échantillonnage de la fonction \(X(\nu)\) est plus fin. On mets autant de 0 que le nombre d’échantillon.

Short Time Fourier Transform¶

Les transformées de Fourier n’indiquent pas clairement comment le contenu en fréquence d’un signal change dans le temps. Cette information est cachée dans la phase. Pour voir comment le contenu en fréquence d’un signal change au fil du temps, nous pouvons découper le signal en blocs et calculer le spectre de chaque bloc.

Elle peut être utilisée pour isoler différentes sources dans un signal. Elle est aussi utilisée pour calculer le changement de phase et de fréquence d’un signal non-stationnaire en fonction du temps.

Le carré de son module donne le spectrogramme. $\( STFT\left\{x[n]\right\} = X(m, \omega) = \sum^{\infty}_{n = -\infty}x[n]w(n-m)e^{(-i \omega n)} \)\( où \)w$ est la fenêtre. Lorsque la fonction de fenêtrage est une fonction gaussienne, la transformée de Fourier à court terme est également appelée transformée de Gabor.

La STFT d’un signal \(x(n)\) est une fonction de deux variables : le temps et la fréquence. La longueur du bloc est déterminée par le support de la fonction de fenêtre \(w(n)\).

La STFT d’un signal est inversible. On peut choisir la longueur du bloc. Plus le bloc est long, plus la résolution de fréquence sera élevée (parce que le lobe principal de la fonction de fenêtre sera étroit). Plus le bloc est court, plus la résolution temporelle sera élevée parce que la moyenne des échantillons est moins élevée pour chaque valeur de la STFT.